I wanted to make a gift for a friend who was elevated to the

Order of the Pelican. Originally, I planned a matching set of embroidered

collar and cuffs for a linen shirt. I finished the collar,but the project stalled before I got the cuffs underway. The recipient recently mentioned to me

that he preferred no cuffs on his shirts to reduce bulk under his doublet. This revelation meant that I had the project already finished and I hadn't known it!

‘Blackwork’ was a popular style of embroidery in the later

part of the SCA period, although the term ‘blackwork’ is misleading as it implies that the embroidery was only

done in black thread. Classic black on crisp white is certainly striking and

was very popular in the sixteenth century, but extant monochrome

embroideries in red, green(Carew-Pole

nightcap), blue (1610 waistcoat,

V&A: 179-1900), purple and pink (1630s woman’s smock at http://costume.dm.net/va/smocks.html) still exist.

Linear monochrome embroidery (often worked in double running stitch) was

popular throughout Europe during the sixteenth century. In fact, this type of

stitchery is so common in Holbein portraits from that time that the

double-running stitch is often called ‘Holbein stitch’.

Monochrome embroidery

(‘blackwork’) is also found in earlier periods in Middle Eastern textiles, and

the geometric shapes found in Tudor blackwork echo similar designs and shapes

found in Middle Eastern embroideries. This fact may have contributed to the

story that Katharine of Aragon brought monochrome embroidery (‘blackwork’) to

England when she arrived to marry Prince Arthur Tudor in around 1501. It is

believed that the occupation of Spanish territories by ‘the Moors’ influenced

design and embroidery, and that ‘blackwork’ or ‘Spanyshe worke’ was introduced

to England by Princess Katharine. Although references to this story are

discussed in ‘Blackwork Embroidery’ by Geddes and McNeill, I have not found any

firm documentary evidence that this story is true. Geddes and McNeill also

quote a line from Chaucer “..embroidery

repeated It’s pattern in the collar front and back, Inside and out…” (p. 25)

which does sound like blackwork, but could also be many other types of

embroidery and so therefore does not clear up the issue. Examination of English

portraiture from the reign of Henry VII and Henry VIII show a marked increase

in blackwork embroidery on clothing during Henry VIII’s reign but we cannot

know if this is due to the introduction of a new stitch technique, copying of a

fashionable Royal or just a new fashion craze. After Henry’s reign, the

Elizabethans took blackwork to a whole new level, with the development of

polychrome counted and non-counted blackwork and the introduction of spangles,

metal threads and raised elements.

The appeal of blackwork was not restricted to England.

Examples of blackwork and similar techniques can be seen in sixteenth century male

and female portraits from around Europe.

This early sixteenth century portrait of A

Lady with Hare by Borgona shows blackwork on the chemise sleeves and neck

edging. This was painted circa 1505 in Toledo. Image from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ladyhare.jpg

This early sixteenth century portrait of A

Lady with Hare by Borgona shows blackwork on the chemise sleeves and neck

edging. This was painted circa 1505 in Toledo. Image from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ladyhare.jpg

The book Moda a Firenze has some wonderful close-up details of blackworked body linens of Italian nobility.

Blackwork can be done in non-counted form, or in counted

form. In counted blackwork, the design is marked out on the background fabric

(traditionally linen) by counting threads and working the design over a set

number of threads, often filling the interior of the design in with a pattern

or repeat. Non-counted blackwork is more free-flowing and involves stitching

over a pre-drawn design. I prefer non-counted blackwork because I dislike

counted work. Double running-stitch is the most common stitch used for

blackwork because it provides an even line that (if done well) is neat and

clean on both the front and the back. A good example of this is shown in the chemise

cuffs of Jane Seymour (next page) as painted by Hans Holbein. Although this

particular example is of counted blackwork, the principle is exactly the same

for non-counted blackwork, and makes the technique ideal for items of clothing

where both sides might show. For example, cuffs, ruff edges, collars etc. Queen

Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d contains ‘The Stowe Inventory’ – a list of

clothes , silks and personal jewels remaining in the Royal residences- which gives

a fascinating and detailed inventory of the types of fabrics and clothing items

that were embroidered, and includes details of colours, jewels, aiglettes and

spangles.

Image from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jane_Seymour

I generally prefer not to do a straight copy of an extant

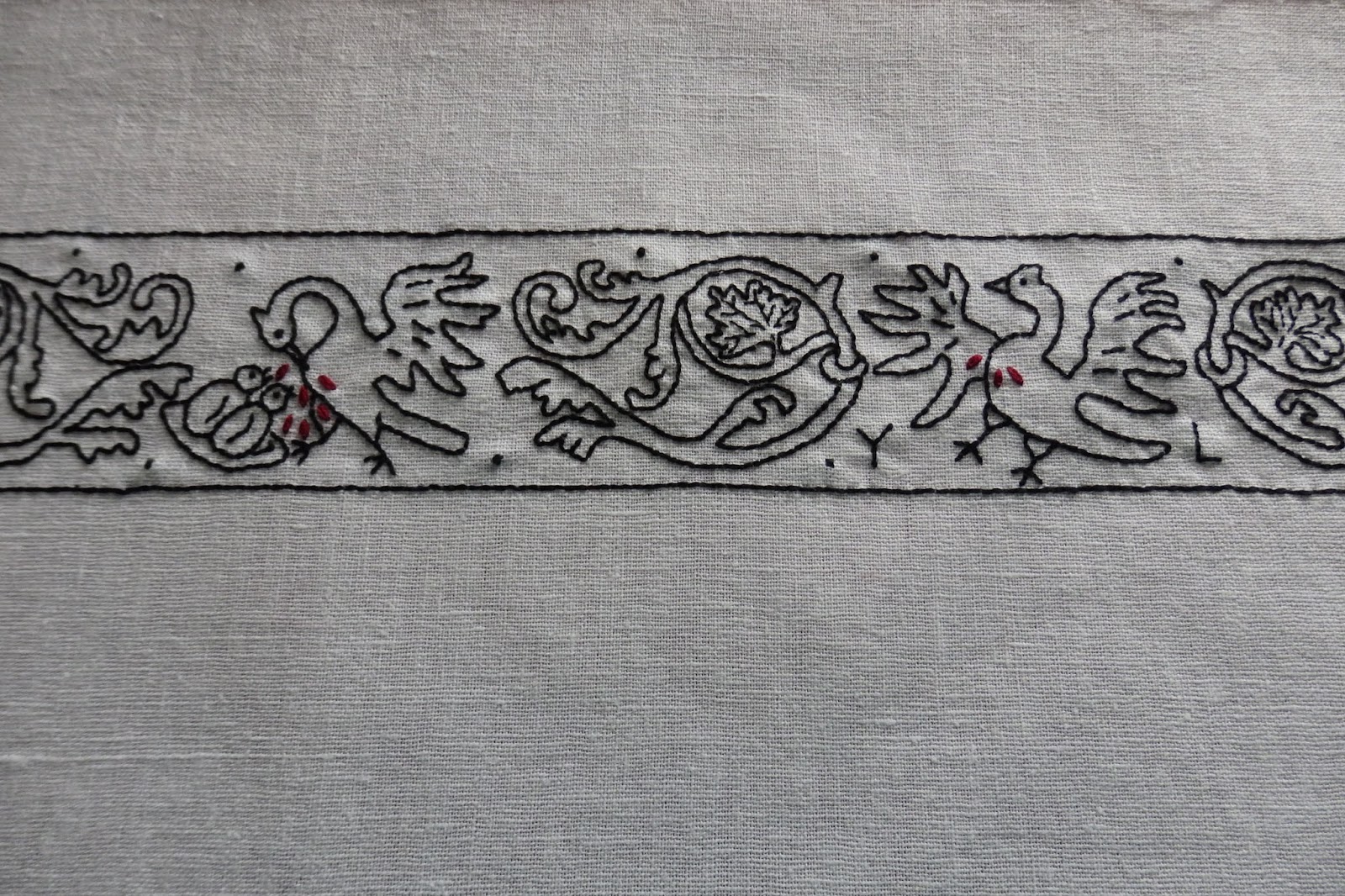

embroidery or period design, and this time I decided to combine some designs

found in the design book Modelbuch aller

art c. 1527. The designs (birds and scrolling floral motifs) that I combined are from plates 2, 3, 7 and 63.

These birds represent ‘Pelicans in their Piety’. This is a

religious motif that was very common in the Middle Ages and Renaissance and shows

the pelican piercing it’s own breast to feed it’s young with it’s blood (a

symbol of the Passion of Christ and the Eucharist [Wikipedia]). In the SCA it has no religious

connotations but signifies the sacrifice and dedication to extraordinary

service demonstrated by those elevated to the Order of the Pelican, and is a

symbol of the Order (and thus a very fitting motif for a gift for a new

Pelican!).

A sketch of my combined, simplified design:

These types of design are very common in the existing sixteenth

century modelbuchs. Close inspection of many of the books show that designs

were probably lifted from one book and reprinted in another, often with little

or no adjustment. This would suggest that many of these designs were widespread

in use in the decorative arts across Europe.

Once my design was ready, I chose my fabric. I used a

cotton/linen blend due to budgetary concerns and availability of pure linen.

Similarly, I used DMC cotton floss rather than silk. Pure linen base fabric and

silk embroidery thread would have been used in period, based on wardrobe

accounts and many extant examples. Although cotton-linen blends were known and used in period

(e.g. as a cotton-linen blend called ‘fustian’) it was heavy, not as commonly available or as cheap as it is today

and was not used for body linens (Tudor Tailor p. 37, Tudor Child p. 61).

Extant linen examples held by the V&A Museum such as the

one below

(Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d, p. 273) show that

embroidery designs were commonly drawn onto the base fabric in ink. I am not confident

enough for that so traced my design out in dissolvable pen ink over a light

source. I used a hoop frame and used two strands of floss. The design is worked

in double running stitch with the addition of decorative knots and maroon

detached buttonhole stitch for the blood drops. Stem stitch or backstitch could

have been used, but I like the neatness of double running stitch and like

knowing that it was used for this type of embroidery in period as evidenced by

Holbein’s portraits. I knot my work on body linens because I tend to throw them in the washing machine, so I work on the expectation that it is likely that others will too.

Once the embroidery was complete, I washed it in lukewarm

water and wool wash, rinsed it, dried it and gently ironed it. I have given it to the recipient to be made into a collar piece for his next shirt.

Here are some images of the front and back of the panel:

Bibliography

Arnold, Janet, 1985. Patterns of Fashion, Pan

MacMillan Ltd, London, UK.

Arnold, Janet, 1988. Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d,

Maney and Sons, Leeds, UK.

Arnold, Janet, 2008. Patterns of Fashion 4, Pan

MacMillan Ltd, London, UK.

Bassee, Nicolas, 1994. German Renaissance Patterns for

Embroidery- A Facsimile Copy of Nicolas Bassee’s New Modelbuch of

1568, Curious Works Press, Texas, USA.

Beck, Thomasina , 1995. The Embroiderer's Story: Needlework

from the Renaissance to the Present Day, David and Charles, Italy.

Catesby, Prudence; 2002. Wrought with flowers of black

silk, Complete Anachronist #115, Spring 2002, SCA Inc, California, USA.

Geddes, Elisabeth and McNeill, Moyra, 1976. Blackwork

Embroidery, Dover Publications Inc, Newy York, USA.

Hayward, Maria, 2007. Dress at the Court of King Henry

VIII, Maney Publishing, Leeds, UK.

Huggett, Jane and Mikhaila, Ninya, 2013. The Tudor Child,

Fat Goose Press, UK>

Mikhaila, Ninya and Malcolm-Davies, Jane, 2006. The Tudor Tailor, B.T. Batsford, London, UK.

North, Susan and Tiramani, Jenny, 2011. Seventeenth

Century Women’s Dress Patterns, V&A Publishing,, London, UK.

Nourry, Claude and Saincte Louie, Pierre, 1999. Patterns

Embroidery: Early 16th

Century, Lacis Publications, California, USA.

Orsi Landini, Roberta and Niccoli, Bruna,2005. Moda a

Firenze, Pagliai Polistampa, Florence, Italy.

Schartzenberger, Johan, 1534/2003. Patterns Book of

Embroidery: 1534, Lacis Publications, California, USA.

Wardle, Patricia; 1970. Guide to English Embroidery, V&A

Museum, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, UK.

Modelbuch aller art (an 1880 reproduction of a 1527

Modelbuch found on the web, link broken)

Web References

Great!

ReplyDeleteWonderful

ReplyDeleteNice

ReplyDeleteAppreciated!

ReplyDelete